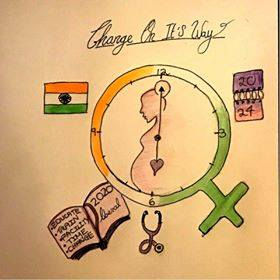

Change is on its way – India’s liberal legalisation of Abortion

- VOICE FOR CHOICE

- Jun 8, 2020

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 12, 2020

Illustrated and written by Sharin Singh (she/her)

TW: this article mentions r-pe and uses gendered language to reflect the law in India

The journey to abortion legalisation in India has been through a tortuous path. Legalised in 1971, but till this day it is considered unsafe to abort there. The 1971 policy has been labelled as a strict injustice in the name of law. The act states abortion is legal in certain conditions: the gestation is under 20 weeks, heavily dependent on the practitioner’s opinion, a risk to the mother’s or foetus health (within the 20-week period) and only available for married women.

10-13% of maternal deaths in India are due to unsafe abortion.

In 2017, a case that involved a 10-year-old girl set fire to the act. The girl at 32 weeks gestation – raped by her uncle- was rejected by the Indian high court to terminate her pregnancy despite the health risk and the abuse. Excuses such as “termination being too risky” and that “she had passed the 20-week mark” were being thrown about. The scale of abuse in India is ou

trageously high, the consequences of such abuse – unwanted pregnancy – for which the termination is also refused. This case is abhorrent on so many grounds, which was recognised by the general public who decided to start a petition for reforming the act.

Furthermore, the ‘Indian Journal of Medical Ethics’ published that 10-13% of maternal deaths in India are due to unsafe abortion. The cause of this was all down to the strict conditions of the act in place. For a woman, passing the 20-week gestation mark, there are limited options: she can illegally abort (probably in an unsafe manner), she can continue the pr

egnancy despite the health risks, or may even consider options such as suicide. For those who survive, they now have a child whom they cannot provide for.

The bill is inconsiderate of rape victims, single mothers, social inequalities and status. The right to abort is split in the country due to the high social inequality gaps. Those in socially deprived areas, are given limited resources and education on this topic. On top of this, there are barely any facilities available for those in need of an abortion. To top it all off, the abortion and other healthcare treatments can be very expensive.

To continue with this injudicious act, it does not mention anything about professional training. Instead, it just openly gives the practitioner the whole power to decide instead of the women. Unexperienced practitioners, the lack of practitioners and the skewed power all in turn raise the death toll due to unsafe procedures.

In light of these recent events, India has decided to change and reform its act this year. The gestation mark is being extended to 24 weeks. This now includes rape victim, victims of incest and minors. It is also available to all women, not just married women (stated in the 1971 act). Furthermore, it adds a no limit to gestation for those who are at risk from continuing the pregnancy. In the coming years, India will have a new set of abortion acts, one with morality and a human face. The next few steps are already being put in place, starting with opening more accessible facilities, providing adequate training and spreading education. This was due to the overwhelming response from the public, the human defence team, medical associations and many more societies who fought for the act to be updated.

From this we learn, difference can be made. Law can be changed; voices can be heard. Justice can be achieved. There is always room for improvement.

Comments